Here’s why we all misjudged the Syrian uprising and war

When Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak was unseated in February 2011, no one in Syria, not long-serving diplomats nor observers on the ground, thought the unrest would spread there. Sure enough, soon thereafter the wheels of the peaceful Syrian revolution started to turn, proving the most experienced experts wrong.

As rebel groups around Syria formed their own small fiefdoms, experts rushed to eulogise Bashar Assad’s rule. Then, particularly following the killing and injuring of leading regime figures in a Damascus bombing in July 2012, there was an undeniable sense, even an expectation, that what happened in North Africa would be replicated in Syria. That, too, proved to be wrong. We now know that the revolution has failed.

Since the experts failed to anticipate the two U-turns that shaped the course of modern Syrian history, what have we learned since? The first conclusion is that experts are, in fact, no such thing. The second is that watching hyperbolic network news skewed our understanding of the reality and complexity of events in individual Syrian towns and districts. This doesn’t explain, however, why most observers, myself included, failed to see the regime holding out.

In retrospect, the Assad regime endured not because it is particularly adept at silencing dissent (although it is certainly that) or because of Russian help but because rebel groups and political elements failed to unite during the initial months of the conflict.

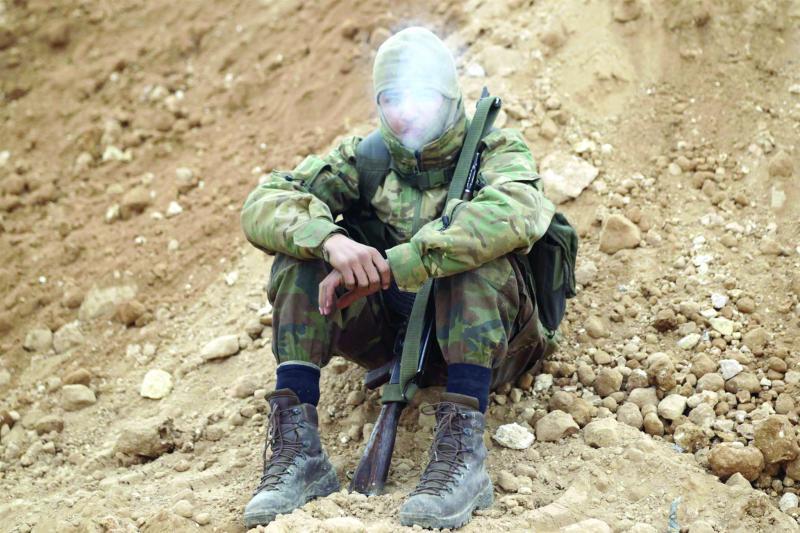

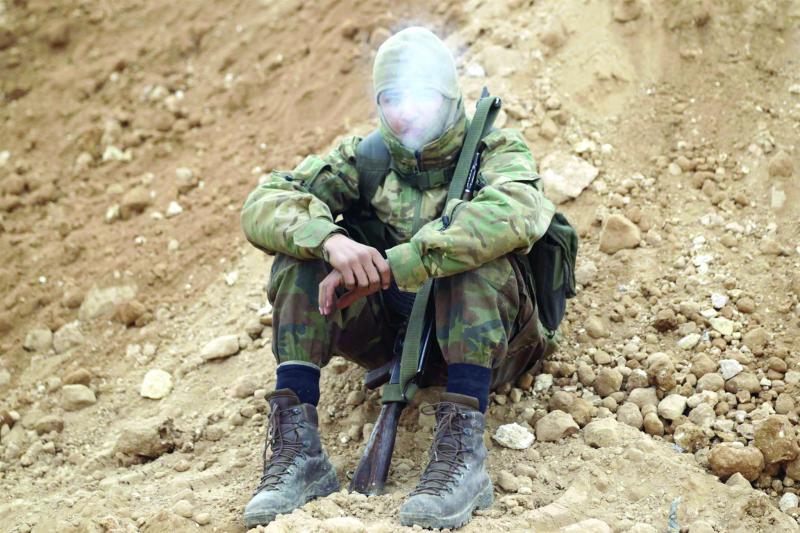

In 2012, it seemed as though every week had a new brigade or rebel group announcing itself on YouTube. The videos were much the same: men in military fatigues hastily reading from a script to the camera. They promised to take the fight to the illegitimate Assad regime and establish a democratic Syria. Behind them would hang a banner depicting the “Free Falcons of Hama Countryside” or some such name of a rebel group.

Thereafter, some rebel groups did establish alliances but these did not last the heat of battle against better-equipped regime forces. Almost all rebel groups drew fighters from their own families and tribes. As we know, that, too, proved a failure.

A 2013 analysis published by the Jamestown Foundation sought to shed light on where the tribal element sat within the conflict. “Tribalism is a socio-cultural fact throughout Syria, not just in the less developed eastern governorates of the country. It is an important form of traditional civil society that will help determine the success of local or foreign-supported security arrangements.” Pertinent words, indeed.

It’s shaky ground, almost an advert for an Edward Said treatise, when Western observers wax lyrically about Middle Eastern tribes and local alliances. However, the cold, hard truth is that the multitude of local rebel groups never aligned. They were, it seems, only interested in controlling their local areas, not in taking the battle to Damascus.

What we can determine, with the rebellion in ashes, is that tribal alliances trumped any desire to establish a unified, nationwide military force capable of defeating the Assad regime. Rebel groups failed to get together because, even at a familial level, divisions abound. Clans within tribes and families within clans regularly stood on opposing sides of the revolution.

Does this mean that Syria and other Middle Eastern societies are less likely to succeed in overthrowing violent dictatorships, particularly one that, in Syria’s case, is so deeply ingrained in the state? There is evidence to support this unfortunate case.

In this context, what’s happened in Tunisia since 2011 has been nothing short of a miracle. It is no value judgment to claim Tunisia has succeeded precisely because its citizens foster a stronger national identity than a tribal one.

What’s clear is that when tribal and national identities are pitted against each other in Syria, the former wins out. That’s why the revolt failed.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.