It is the Iraq invasion that will define Kofi Annan

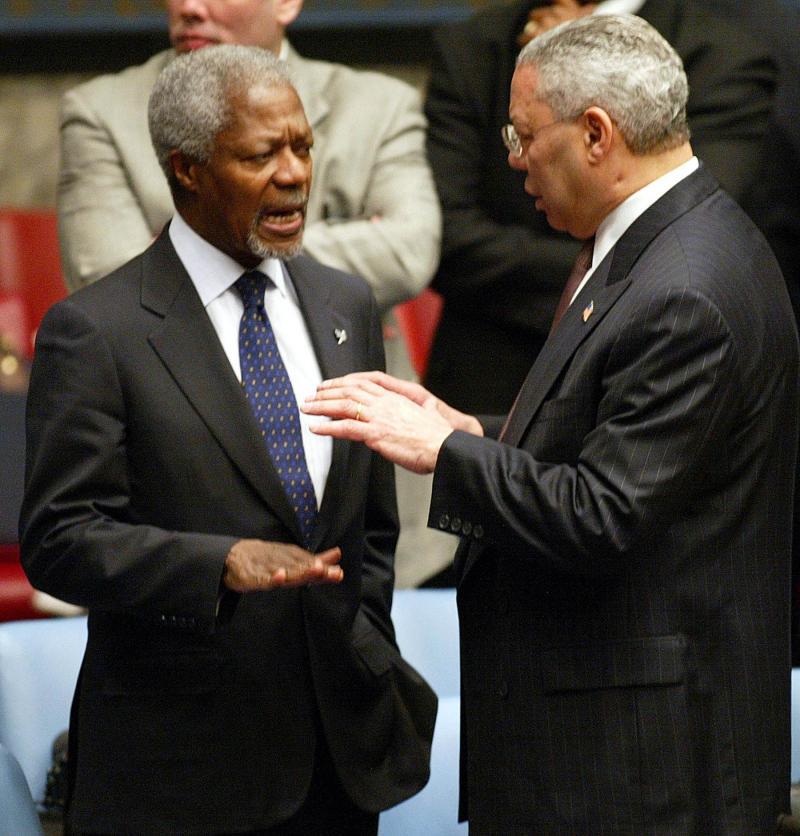

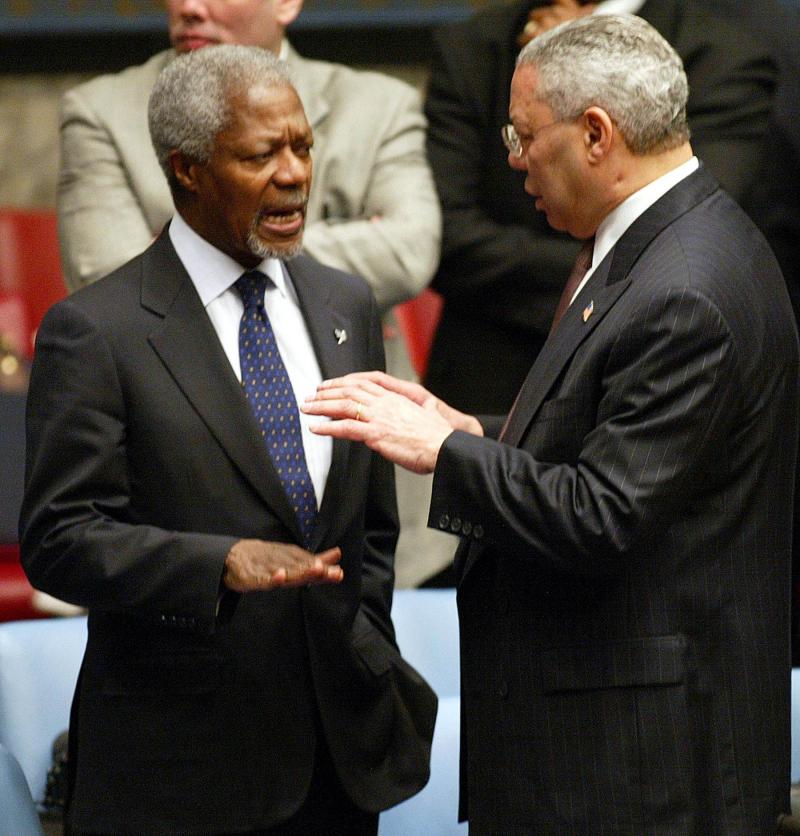

The death of Kofi Annan, UN secretary-general during one of the organisation’s most tempestuous and spectacularly ineffectual phases, brings back bad memories. The Iraq invasion of March 2003 happened on Annan’s watch. Eighteen months later he had the guts — as well as the effrontery — to publicly admit it was “illegal.”

He never explained why he hadn’t said so at the time, why he stayed on in his job despite being unable to prevent a crime against international law, the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives, enormous human suffering and continuing regional tumult.

That partial, somewhat skewed moral clarity is seen to define Annan, the United Nations itself and perhaps the very notion of a just and international system. Annan’s death simply underlines the strength of the old order. Chances are the United Nations would, yet again, do nothing if the United States decided to make war on a sovereign nation such as Iraq, using a made-up pretext and without UN Security Council authorisation.

Just as in Annan’s time 15 years ago, the United Nations would posture and plead, purse its lips and fall silent, only to acknowledge, months later, the illegality of the war. This is dispiriting because the possibility of another Iraq, under a different UN secretary-general and US president is ever present.

Donald Trump’s administration is unremittingly hostile towards Iran. In May, Trump withdrew the United States from the multilateral nuclear deal even though the International Atomic Energy Agency said Iran was implementing its nuclear-related commitments. In August, Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, urged Iran to comply with Trump’s conditions for talks but these were described by former US Envoy in Tehran John Limbert as unrealistic and more akin to seeking “a surrender (than) an agreement.”

With Trump under pressure from a special counsel investigation into his election campaign and conduct in office, the drums of war could start up again to change the public focus. Would Antonio Guterres, who now holds Annan’s job, do anything different?

Was Annan’s failure that of the man or of the system over which he presided? Is the UN secretary-general a figurehead of a defunct post-second world war order? The UN secretary-general’s job is described as that impossible thing, a “secular pope.” Did Annan, the second African after Egyptian Boutros Boutros-Ghali and the first sub-Saharan African to lead the United Nations, embody the organisation’s greatness as well as its great weaknesses?

There are no clear answers but the United Nations today faces much the same challenges as under Annan. Since the Iraq invasion, the United States has been challenging Annan’s view of the United Nations as “the sole source of legitimacy” for foreign intervention. Trump, just as much as George W. Bush, pooh-poohs the United Nations and is aggrieved about paying into its budget. And this US president more than any other disdains international cooperation and multilateralism.

The Iraq war, more than almost anything else, exposed the hollowness of the moral authority wielded by the United Nations. Eight years after the invasion, Annan had this to say about his “darkest moment” when he realised that George W. Bush’s America, Tony Blair’s Britain, John Howard’s Australia and Leszek Miller’s Poland would be going ahead with military action.

“I worked very hard. I was working the phone, talking to leaders around the world,” he said. “The US did not have the support in the Security Council. So they decided to go without the council. But I think the council was right in not sanctioning the war. Could you imagine if the UN had endorsed the war in Iraq, what our reputation would be like?”

Those comments to Time magazine in February 2013 underscore Annan’s concerns as the world’s foremost diplomat. As a good bureaucrat, he cared about good process in policy battles and about bad publicity. This, some would say, is the problem with the United Nations itself.

As Guterres, his successor once removed, has said: “In many ways, Kofi Annan was the United Nations.”

Rashmee Roshan Lall is a regular columnist for The Arab Weekly. She blogs at www.rashmee.com and is on Twitter @rashmeerl

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.