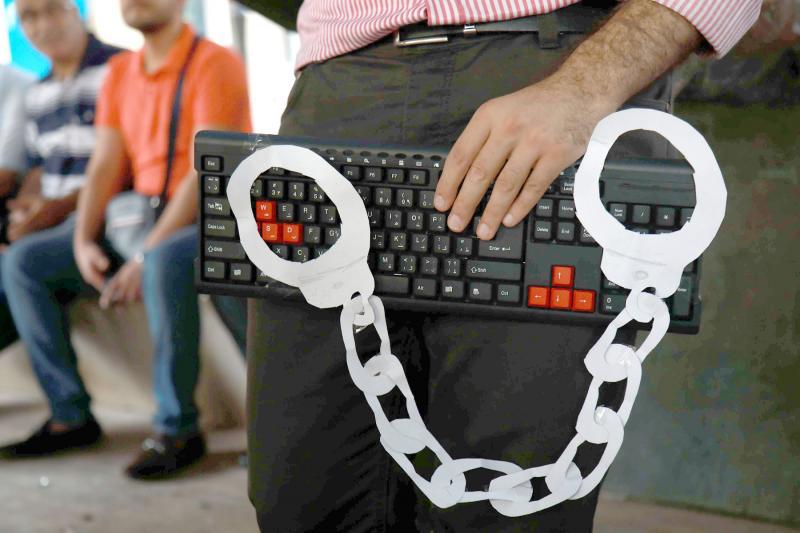

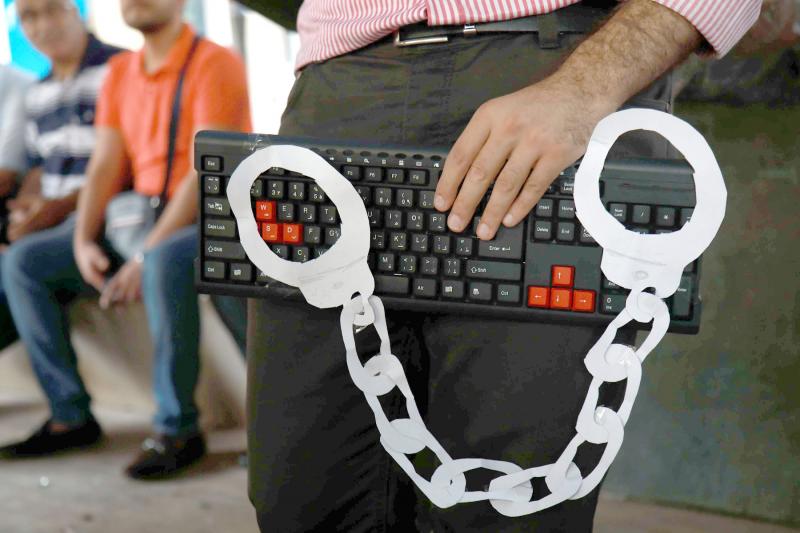

Lebanon’s shrinking freedom of expression

BEIRUT - More than seven activists have recently been summoned by Lebanese intelligence services because they posted social media comments critical of pro-Syrian and Iranian-Lebanese politicians and parties. In the past two years, human rights groups have reported a threefold increase in the arrest, prosecution and questioning of activists and journalists.

The Lebanese penal code punishes libel and defamation of officials, a justification that appears to be increasingly deployed by security officials to question and prosecute activists or harass disgruntled citizens venting their frustration on social media.

Rawane Khatib and Khaled Abbouchi were summoned July 24 by the Lebanese office for cybercrime. They were accused of publicly criticising Lebanese President Michel Aoun and his son-in-law, Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil.

In itself, that’s notable. However, it falls within the context of a wider security crackdown by Lebanese intelligence services, targeting people denouncing the actions of specific parties, activists say.

“Arrests and summoning (for interview) targets activists or journalists critical for the most part of Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, followed by President Aoun and Hezbollah,” said Widad Jarbouh, a researcher at the SKeyes Centre for Media and Cultural Freedom at the Samir Kassir Foundation.

Mohammad Awwad, an activist known for articles disparaging Hezbollah, was arrested by the Lebanese General Security. He was released after he signed a document forbidding him from criticising the three main political positions in Lebanon — the president, prime minister and the parliamentary speaker — as well as various religious figures.

Also in July, Elie el-Khoury, 25, was summoned by Lebanon’s cybercrimes bureau for questioning. Khoury had complained about the poor level of public services in Lebanon and accused Aoun of turning the country into his “family home.”

When Khoury’s lawyer intervened, the cybercrime bureau rescinded its request without explanation, Lebanese website Naharnet said.

Journalist Fidaa Itani was sentenced in absentia to four months in prison and fined 10 million Lebanese pounds ($6,550). Itani had called out Bassil on Facebook over his alleged racist policies towards Lebanon’s Syrian refugees.

The journalist, who is also a Hezbollah opponent, uncovered numerous cases of potential corruption in which Bassil was implicated.

Other infamous cases targeting activists and journalists include the prosecution of researcher Hanin Ghaddar affiliated with the Washington Institute. In April, after intense lobbying from both local political figures and the US Embassy, sources close to the matter said, the Military Tribunal reversed its verdict, referring the case back to the Military Prosecution.

The tribunal’s decision came after Ghaddar’s lawyer filed an objection to the court’s decision to sentence her client in absentia to six months in prison for comments critical of the Lebanese Army. A vocal critic of Hezbollah, Ghaddar accused the army of distinguishing between Sunni and Shia militants, suggesting it was more tolerating of the latter.

That same month, First Investigative Judge Ghassan Oueidat issued an arrest warrant for journalist Maria Maalouf for slandering Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah.

However, elsewhere, Jarbouh noted, other segments of the population, typically those associated with parties aligned to Iran and Syria who threaten and attack activists remain untouched. “As an example, individuals who voiced death and rape threats against an American University student who was filmed protesting against the Syrian regime offensive on Aleppo two years ago were never summoned by authorities,” he said.

In May, another critic of Hezbollah, Ali al-Amin, who was running as an independent in parliamentary elections against the organisation, was severely beaten. Amin is a Shia journalist and director of the news website “Al Janoubia” (“The South”). The perpetrators of the crime are yet to be identified.

“To date, most of the summons and arrests are the work of the office for cybercrime, the general security and the Lebanese army intelligence,” says Jarbouh.

SKeyes estimates that, over the past two years, arrests targeting activists and journalists increased from 10 to 30 per year. The rise in power of pro-Iran and pro-Syria figures in parliamentary elections appears to have translated into a shrinking of freedom of expression and repressive measures in Lebanon.

Mona Alami is a French-Lebanese analyst and a fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East of the Atlantic Council. She lives in Beirut.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.