Turkey sees advantages and risks in Khashoggi case

ISTANBUL - The disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul could hurt Turkey’s image at a time when Ankara is trying to improve relations with the West.

Khashoggi, a journalist who was close to the Saudi court and intelligence establishment before becoming a critic of Riyadh's policies, was last seen October 2 when he entered the Saudi Consulate to process paperwork for his planned wedding with a Turkish woman.

Since then, Turkey’s security forces have leaked information to national and international media that suggest Khashoggi was killed inside the consulate.

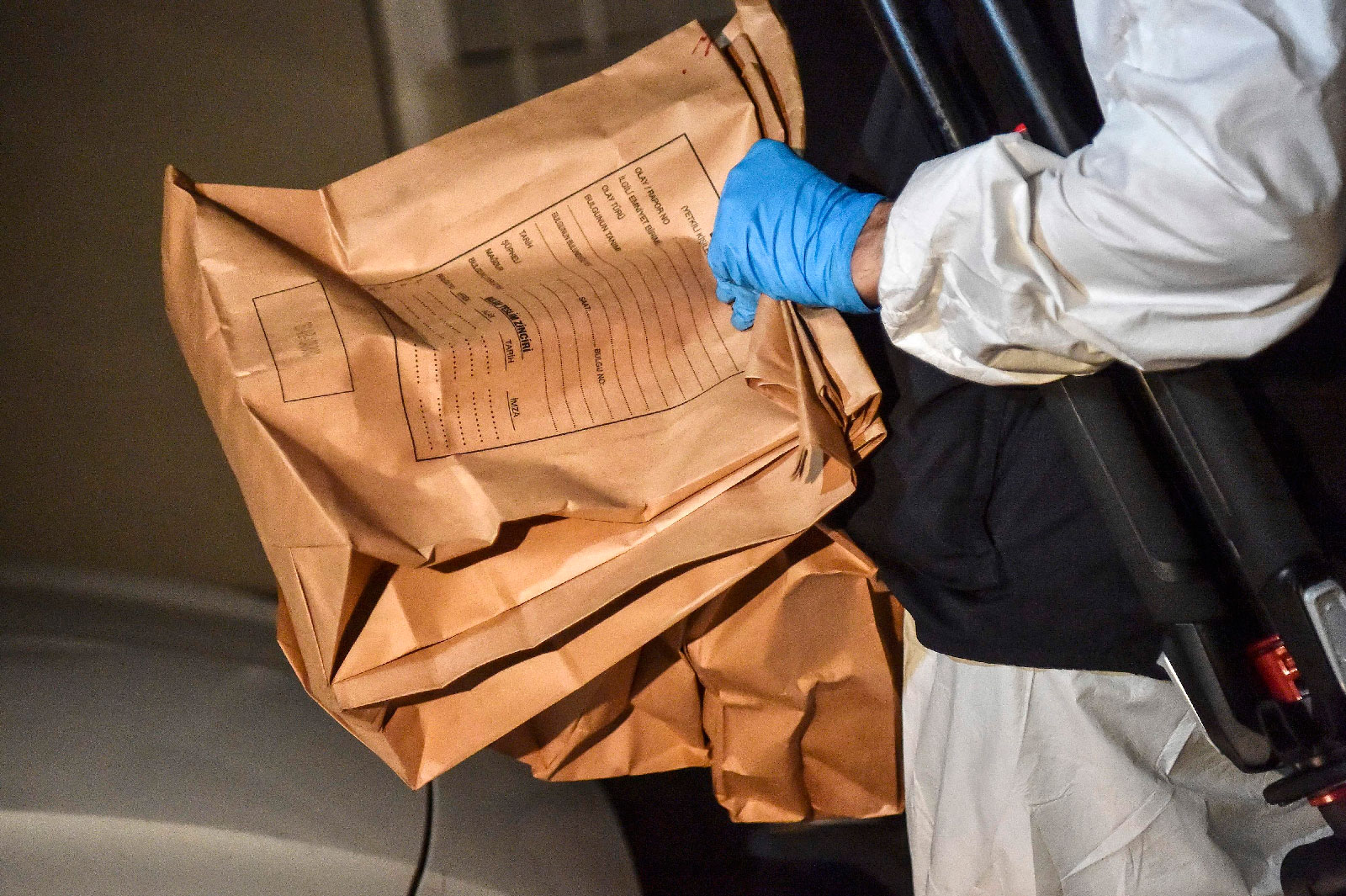

Turkish police searched the building on October 16 in an investigation that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said was focusing on toxic materials. “My hope is that we can reach conclusions that will give us a reasonable opinion as soon as possible because the investigation is looking into many things such as toxic materials and those materials being removed by painting them over,” Erdogan said.

Erdogan, known for his harsh rhetoric both in domestic affairs and in international relations, did not accuse the Saudi leadership of involvement in Khashoggi’s suspected death. His approach suggested that Turkey, whose relations with Riyadh are strained because of Ankara’s close ties to Qatar and because of Turkish support for the Muslim Brotherhood, has so far seemed less interested in pouring more oil onto the fire than in enabling Turkey to take advantage of the crisis.

Middle East analyst James M. Dorsey wrote in his blog that Turkey was using the issue to "enhance its geopolitical position vis-a-vis Saudi Arabia as well as Russia and Iran and potentially garner economic advantage at a time that it is struggling to reverse a financial downturn."

"One immediate Turkish victory," he added, "is likely to be Saudi acquiesce to Mr Erdogan’s demand that Saudi Arabia drop its support for Kurdish rebels in Syria that Ankara sees as terrorists -- a move that would boost Turkey’s position in the Turkish-Russian-Iranian jockeying for influence in a post-war Syria. Turkey is also likely to see Saudi Arabia support it economically."

Dorsey quoted international relations scholar Serhat Guvenc as saying that Turkey "wants to back Saudi Arabia to the wall. (It wants to) disparage the 'reformist' image that Saudi Arabia has been constructing in the West.”

The Khashoggi case is not the first suspected killing of a foreign dissident on Turkish soil. Approximately a dozen activists from the former Soviet Union have been killed in Turkey in recent years, the BBC reported. In the latest case made public, Ruslan Israpilov from Chechnya was killed in front of his house in Kocaeli, south of Istanbul, two years ago.

Activists from Chechnya and other regions of the former Soviet Union say Russian intelligence agents have been behind the killings but Ankara has been careful not to let the incidents lead to a crisis in relations with Russia, a key supplier of natural gas and an increasingly important political partner in Syria and elsewhere.

Kerim Has, a Moscow-based analyst of Russian-Turkish relations, said Ankara quietly exchanged suspected Russian agents, arrested for alleged involvement in the killings, for leaders of the Crimean Tartars, a Turkic ethnic group on the peninsula annexed by Russia in 2014, who were jailed in Russia.

The cautious response displayed by the Turkish government since Khashoggi’s disappearance echoed Ankara’s handling of the Russian cases, Has said. “There are similar patterns,” he added.

By trying to prevent a full-blown crisis in relations with Saudi-Arabia, Turkey could face other difficulties. The country, especially Istanbul, is host to many journalists, activists and politicians from Arab nations, mainly Islamists, who disagree with their governments back home.

Yasin Aktay, a senior official of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, Erdogan adviser and a friend of Khashoggi’s, said, for many Arab journalists, the alternative to living in Turkey was “prison in their country,” Agence France-Presse reported. “What happened to Jamal Khashoggi aimed to maybe send a message to them that they are not safe here but Turkey remains a safe country,” Aktay said.

A perception that foreign Islamists are not safe in Turkey would have an unwanted fallout on Erdogan's regional alliances based at least in part on his domestic and regional affinities with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Any attempt to cover up responsibilities in the Khashoggi case could also backfire on Turkey, which is careful not to be perceived as a place where suspicious deaths of reporters and activists are not accounted for.

If the country acquires a reputation for being a “convenient address” for the killing of foreign dissidents, its international image could suffer, Has said. “It may deteriorate more if the case is silently closed between Turkish and Saudi authorities and no high-ranking Saudi official, diplomat or statesman is found responsible.”

Turkey’s restrictions on free speech pose another challenge in the light of the Khashoggi case. Dozens of journalists, activists and opposition politicians have been jailed for what critics of Erdogan say are political motives aimed at silencing dissent. Reporters Without Borders, a group campaigning for media freedom, ranks Turkey 157th out of 180 countries in its “2018 World Press Freedom Index.”

A crackdown on suspected government foes following a coup attempt in 2016 triggered accusations by the West of a growing autocracy in Turkey, which led the Erdogan government to try to improve its image. Turkish cabinet ministers have restarted work on a reform agenda designed to bring the country closer to the European Union. During a visit to Germany in September, Erdogan vowed to leave past tensions behind and open a new page in relations.

However, in a development that highlighted Turkey’s difficulties, a court in Istanbul said on October 16 that the government should ask the international law enforcement agency Interpol to issue an arrest warrant for two prominent anti-Erdogan journalists. The court wants Can Dundar, who lives in Berlin, and Ilhan Tanir, who is in the United States, to face charges of espionage in a trial initiated after Dundar’s newspaper accused the Turkish government of shipping weapons to Syrian rebels.

Erdogan critics say Turkish government officials were acting hypocritically in the Khashoggi case. “It’s a bit off that they are getting involved in this in the first place, given the fact that they are the number one jailer of journalists in the world,” Middle East expert Jonathan Schanzer told the Australian network ABC.

Schanzer, a senior vice-president of research at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington think-tank, added that Turkey had engaged in “illegal renditions” of suspected dissidents from other countries.

Turkish officials said in April that 80 Turks suspected of ties to a group seen as the driving force behind the 2016 coup attempt had been seized abroad and returned to Turkey.

Thomas Seibert is an Arab Weekly contributor in Istanbul.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.