Locusts, coronavirus a dual threat in Horn of Africa

LONDON - As the world is preoccupied with battling the deadly coronavirus pandemic, which has disrupted economies worldwide and forced millions of people into lives of quarantine and self-isolation, states in East Africa and the surrounding area are bracing for new locust swarms that could have an even more destructive impact than the invasions that have descended on the region since last year.

The United Nations had already warned that the coronavirus crisis was poised to disrupt global food supply chains and create increased pressure on states that struggle for food security. In its latest Locust Watch report, the UN's Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) warned that those pressures would be compounded in East African states including Sudan, Somalia and Ethiopia as the formation of new locust swarms "represents an unprecedented threat to food security and livelihoods because it coincides with the beginning of the long rains and the planting season."

According to the FAO, "the potential for destruction is enormous. A locust swarm of one square kilometre [around 150 million locusts] can eat the same amount of food in one day as 35,000 people."

Billions of desert locusts, some in swarms the size of Moscow, have already chomped their way through much of East Africa, including Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Djibouti, Eritrea, Tanzania, Sudan, South Sudan and Uganda.

There have been particularly large swarms in Gulf countries including Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and Iran, after their breeding was spurred by one of the wettest rainy seasons in the region in four decades.

In Ethiopia, the locusts have caused widespread losses of sorghum, wheat and maize and vastly reduced the amount of available land for cattle grazing, the FAO said. It said the swarms have damaged 200,000 hectares of cropland and driven around a million people to require emergency food aid.

Some 75 percent of Ethiopians requiring emergency food assistance live in the country's Somali and Oromia regions. FAO Ethiopia representative Fatouma Seid said farmers and pastoralists needed help in the form of agricultural inputs and cash transfers to get them through the emergency, which was being worsened by the coronavirus pandemic.

"It is critical to protect the livelihoods of the affected population especially now that the situation is compounded by the COVID-19 crisis," Seid said, referring to the disease caused by the coronavirus.

The FAO has warned that the destruction caused by the locusts could have a devastating impact on the Horn of Africa region, where "the vast majority of the population depend on agriculture for their livelihoods (for example, up to 80 percent of the population in Ethiopia and 75 percent in Kenya)."

Officials in states hit by the swarms have said that the global lockdowns to combat the coronavirus have hampered efforts to fight the locusts. The huge swarms frequently move across borders even as cross-border travel restrictions are being strengthened by governments and deliveries of crucial pesticides are held up. Uganda’s agriculture minister recently told the Associated Press (AP) that authorities are unable to import enough pesticides from Japan, citing the coronavirus' disruptions to international cargo shipments.

Cyclones, viruses and plagues

The swarms that emerged in the region in February had evolved into a much larger problem due to the impact of climate change. Cyclone Mekunu, a tropical storm that struck the Arabian Gulf region in 2018, created the ideal conditions for several generations of locusts to breed in the Empty Quarter, a vast desert region that stretches across Saudi Arabia, Oman and Yemen.

However, the amount of locusts produced during that breeding season would increase alongside an increase in cyclonic storms, which experts attribute to the impact of climate change. An increase in the number of cyclones meant that there were longer periods of moist sand and vegetation in the desert region, which allowed the number of locusts to increase exponentially.

The ability to fight the swarms was hampered by other man-made factors, most significantly the civil war raging in Yemen, a country considered a "frontline" for locust outbreaks with the insects present throughout much of the year. But as fighting rages in the country between an Iran-backed rebel group and the government - backed by a Saudi Arabia-led coalition of states - damaged infrastructure and rival systems of governance have made it difficult to maintain an effective locust control programme, allowing swarms to thrive and spread from Yemen to neighbouring states.

Yemen is already heavily reliant on food imports and the population is on the brink of famine, which could potentially lead to a devastating impact on vulnerable communities considering the threat of locusts to agricultural land and the ongoing effects of the country's civil war. A similar situation exists in Somalia, which also faces heavy security challenges and where the breeding time of the insects was similarly extended due to an unseasonable cyclone in December 2019, then compounded by authorities' difficulty in bringing their numbers down.

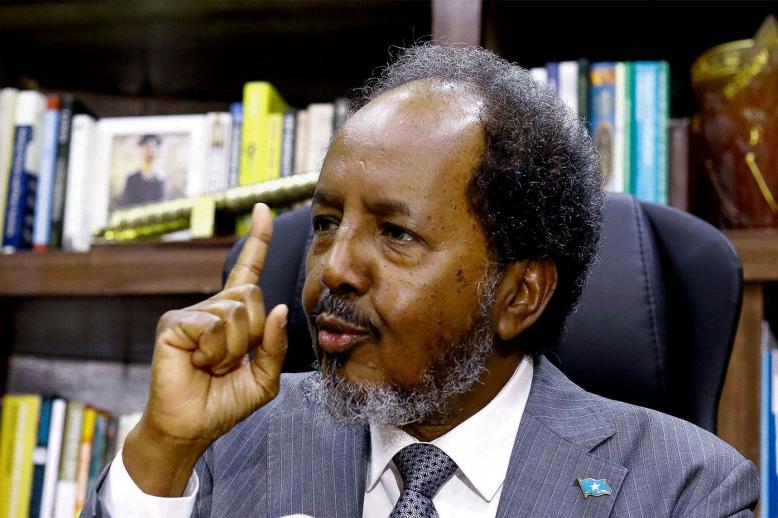

Somalia has since declared the locust swarms a national emergency. Many Somalis rely on a pastoral way of life for their incomes, and the locusts threaten to destroy all the pasturage for farmers' livestock. That could potentially lead to economic devastation as well as increased malnutrition in communities that grow their own food.

The FAO has requested $140 million in aid in order to battle the locusts, an increase from its request in January for $76 million. It says it has targeted 1 million hectares of land for "rapid locust surveillance" in eight states: Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania, where 20.2 million people face severe acute food insecurity, alongside a further 15 million people in Yemen.

But the battle against the locusts is sure to be affected in coming months by the coronavirus pandemic, amid fears that the two crises could exacerbate each other and lead to an even more devastating impact for vulnerable populations.

Yoweri Aboket, a farmer in Uganda, was quoted by the AP news agency as saying, “once [the locusts] land in your garden they do total destruction. Some people will even tell you that the locusts are more destructive than the coronavirus. There are even some who don’t believe that the virus will reach here.”

But FAO officials say they are encouraged by the urgency governments have shown in preventing the formation of an all-out "plague" of locusts, even amid the global pandemic. A locust invasion would be considered a plague if it reaches the point where human intervention is no longer effective at containing the insects' spread.

"There is no significant slowdown because all the affected countries working with FAO consider Desert Locusts a national priority," said Cyril Ferrand, the FAO's Resilience Team Leader for East Africa.