US-Iran rivalry puts Iraq back at the centre of regional turbulence

BAGHDAD – Iraq once again finds itself in the eye of a gathering storm, where domestic paralysis converges with intensifying external pressure and the spectre of regional war looms ever closer. After decades defined by invasion, insurgency and political fracture, the country had begun, haltingly, to recover a measure of normalcy. That fragile equilibrium is now under strain, as Iraq struggles to reconcile its internal divisions with the competing gravitational pull of its two most powerful external patrons: the United States and Iran.

Since parliamentary elections last November, Iraq’s political life has revolved around a single unresolved question: who will form the next government? The Coordination Framework, an umbrella alliance of Shia parties with varying degrees of proximity to Tehran, has put forward Nouri al-Maliki as its candidate for prime minister. Maliki, who governed Iraq for two terms between 2006 and 2014, remains one of the most divisive figures in the country’s post-2003 history, initially elevated with American backing, later estranged from Washington amid deepening ties to Iran and accusations that his rule entrenched sectarianism.

Washington has been unequivocal in its opposition. US President Donald Trump signalled that Maliki’s return would come at a price, warning that American political and economic support for Iraq could be curtailed. Trump also framed the issue in stark terms, leaving little doubt that Maliki’s candidacy is viewed in Washington through the prism of Iran. As Iraqi analyst Ihsan al-Shamari observes, “The Trump administration does not distinguish between Iraq and Iran; it treats them as a single, inseparable strategic problem.”

That external pressure has sharpened fault lines within Iraq’s political elite. Some figures inside the Coordination Framework argue for restraint, urging Maliki to step aside in order to shield the country from punitive measures and renewed confrontation with Washington. Others reject such calculations outright, insisting that yielding to American pressure would hollow out Iraqi sovereignty and entrench foreign tutelage. A source close to Maliki maintains that he is not seeking escalation, but rather an accommodation with the United States, one that acknowledges the constraints of the moment and the need for careful, time-consuming diplomacy.

The stakes extend far beyond political symbolism. Iraq’s oil revenues, which underpin more than 90 percent of the state’s income, are largely channelled through accounts in the United States, giving Washington formidable leverage over Baghdad’s economic lifelines.

The outgoing government of Prime Minister Mohammed Shiaa al-Sudani has invested heavily in cultivating relations with Washington, viewing American backing as essential for attracting foreign investment, particularly in the energy sector. Any disruption to that relationship, whether through sanctions or financial restrictions, would reverberate through an economy already struggling to sustain public services and meet salary obligations that affect millions of Iraqis.

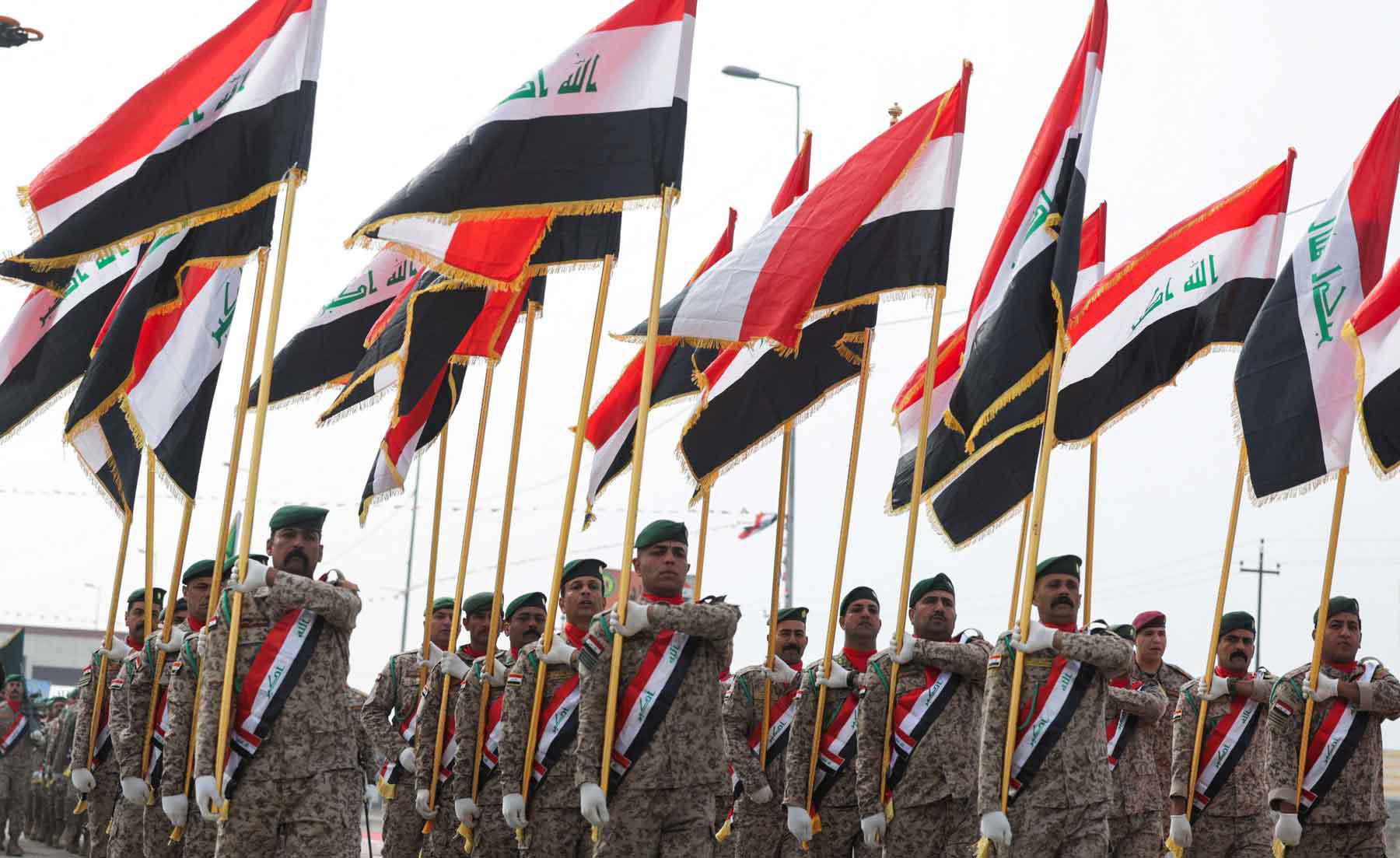

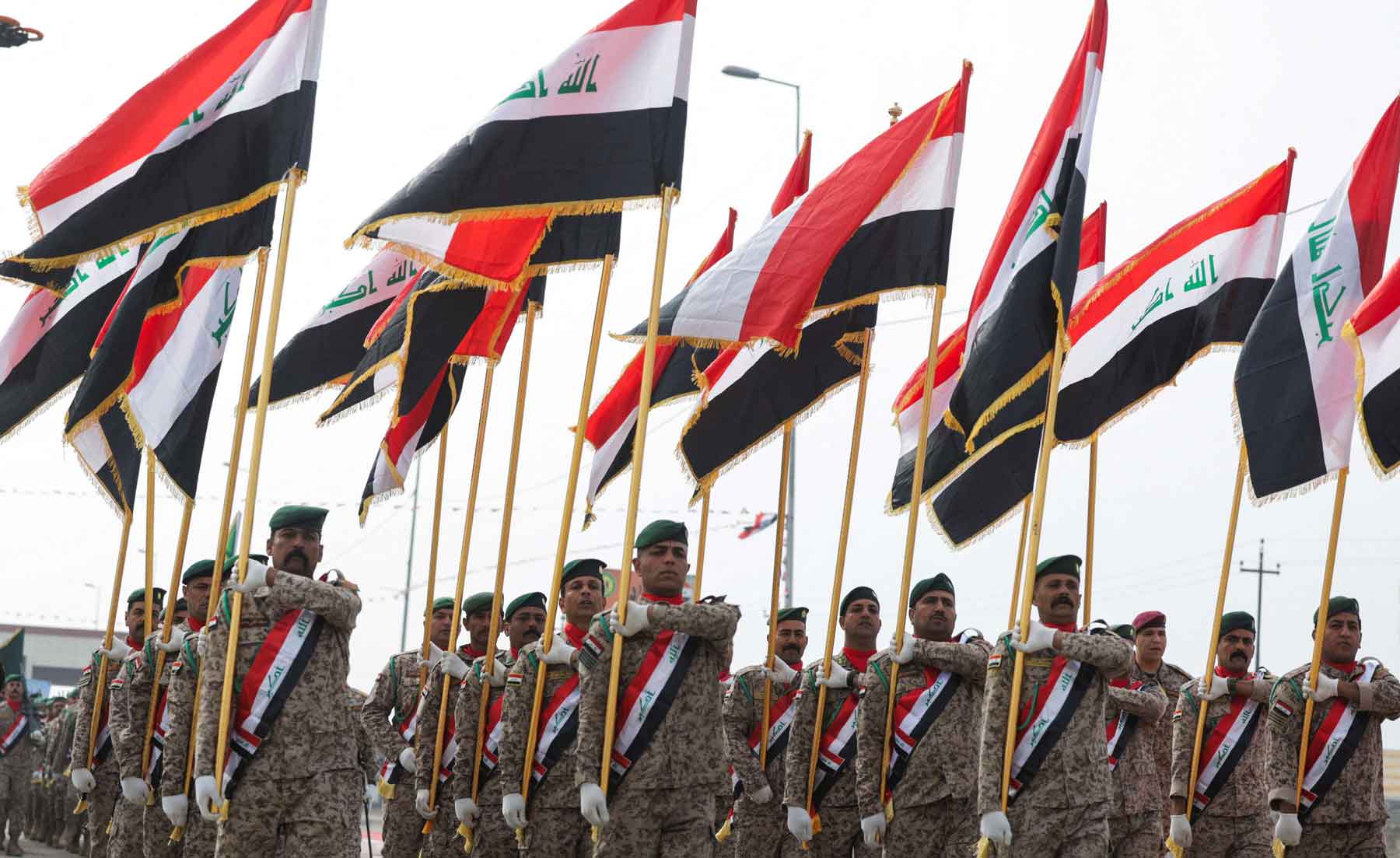

Yet Iraq’s geopolitical predicament cannot be reduced to its relationship with the United States alone. Tehran’s influence remains deeply embedded in the country’s political and security architecture. Iran-backed factions wield power both within parliament and beyond it, through armed groups that operate under the umbrella of the Iraqi state while retaining their own chains of command. Several of these groups, already under US sanctions, have declared their readiness to mobilise in defence of Iran should it come under attack.

With Trump again raising the possibility of military action against Tehran, analysts warn that Iraq could be drawn unwillingly into a broader confrontation, whether as a launchpad, a battlefield or a theatre for retaliatory strikes.

“The danger,” Shamari cautions, “is that Iraq becomes a space for regional escalation. Iran-aligned forces would face a struggle for political and military survival, reshaping the country’s internal balance of power.”

The implications are sweeping. Beyond elite manoeuvring and cabinet arithmetic lies the risk of economic isolation, institutional erosion and the transformation of Iraqi territory into a proxy arena for a conflict not of its choosing. For ordinary Iraqis, the fear is painfully familiar: that years of incremental recovery, tentative reform and relative calm could be undone by forces beyond their control.

At its core, Iraq’s predicament lays bare a recurring dilemma of its post-2003 existence: how to assert sovereignty while navigating the rival demands of regional and global powers. As tensions rise across the Gulf and the wider Middle East, Iraq’s leaders are attempting to thread an increasingly narrow needle, balancing domestic cohesion, economic survival, and the influence of powerful allies in a country that has paid too dearly for instability to afford another descent into chaos.